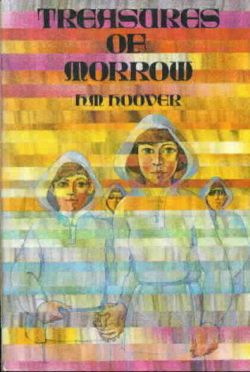

Treasures of Morrow picks up immediately after where Children of Morrow left off, as Tia and Rabbit journey by slow, slow, boat down to the beautiful welcoming wonders of southern California. (It’s good to know that after an ecological apocalypse, southern California will survive, and its bounty soon regained. No exact word on how it survived earthquakes—a small subplot in this book—but let us not quibble over geology.) Unlike the first book of this duology,Treasures of Morrow is less about the sort of brutal society that might arise following an ecological attack, and more about how two members of that brutal society might, or might not, fit in with a society that was, as we are too frequently informed, saved by their superior foresight and belief in the One, or the balance of life.

Tia and Rabbit spend the first half of the book adjusting, or trying to adjust, to their new, nearly perfect world. This, alone, might have been an interesting book, exploring the different attitudes of the two cultures, but Hoover decides not to leave it there, instead having the Morrows take a second trip back to the brutal missile base, this time for some anthropological fieldwork, instead of a rescue attempt.

This leads to several questions: if the Morrows wanted to do actual anthropological fieldwork (although much of what they end up doing would make most anthropologists blanch, and certainly horrify the Federation from Star Trek), why not do it while they were already out there on the first trip, instead of subjecting Tia and Rabbit and limited fuel resources to two trips? Why force Tia and Rabbit to revisit the place where they were repeatedly emotionally and physically abused, especially since the mere thought of returning—and the actual trip—gives Tia nightmares?

I have an answer, and it’s not a particularly nice one, nor the one given by the Morrows. They claim that this trip will finally show Tia, once and for all, that the abusive part of her life is over—although exposing her to these abusers, and actually putting her (again) in physical danger from the abusers hardly seems the best way to approach this. The reality seems a bit different. Tia, understandably, has noted and begun to resent the superior attitudes of the Morrows, noting that none of them would be able to survive what she and Rabbit did. She also observes that the Morrows fail to understand just how lucky they are—they don’t consider their advantages luck, but just the way the world is—another resentment.

It’s the first acknowledgement, however briefly, of how deeply annoying the constant superior attitude of the Morrow community is. Even if they have all of these cool telepathic powers and parrots and cats named Elizabeth and Essex. (Elizabeth is the older cat, followed around by Essex. Tia and Rabbit and I suspect many young readers fail to get the joke, not helped when Hoover points out that Tia and Rabbit are not getting the reference.)

But, although most of these thoughts supposedly occur only in Tia’s private thoughts, the Morrow community is a community of telepaths. Which suggests that Tia and Rabbit are dragged along on this return trip to show them just how lucky they are—a nice object lesson that nearly results in their death, and does result in Tia finding out that her mother is more than willing to kill her.

This happens largely because the missile silo people are as appalled by the Morrow community as the Morrow community is appalled by them. After all—and this is important—the Morrow community arrived, raped one of their women, returned and killed their leader and various hunting men, and now, on this third trip, cap things off by, yes, destroying the missile silo and issuing a rather inadequate apology about this.

And they can’t seem to understand why the now-formerly missile silo people aren’t delighted to see them.

Actually, I misspoke a little there: to really cap things off, the Morrow community decides that although they have abundant food, clean water, and better air quality and higher oxygen levels (the missile silo community lives at a higher altitude) the best thing they can do is leave the now-formerly-missile-silo community in abject misery and considerably more physical labor now that they’ve done their (very limited) anthropological research. Er. Yay. This only a few pages after we have been assured that the supposedly more primitive community is genetically equivalent to the Morrow community. (An odd statement, given that the earlier book suggested that all of the shellfish eating had changed Morrow genetics and given them telepathy.)

At Tia and Rabbit’s request, the Morrow community does consider rescuing one member of the missile silo community—a woman who had previously shown kindness to Tia, and who declines the invitation. And they do also offer some fire fighting assistance. (Nice, given that the fire would not have happened had they not shown up.) But that’s about it. I also find it odd that the (self-named) anthropologists of the group have no interest in seeing what happened to the missile-silo community after the destruction of their object of worship; it would seem to be a perfect case study. Then again, I can also understand why everyone decides that really, this trip isn’t working out and they should go home.

The visit back to Tia and Rabbit’s old home is a pity, not just because of the questionable ethics involved, but because it interrupts a book that did have an interesting, if often seen premise: just how do you adjust to a new world that offers so much more than your last world—and yet is unaware of just how fortunate it is? In a situation, moreover, where your old home and this new one are literally your only two options: no other place on the planet yet offers breathable air, reliable food supplies or other people. And in turn, how do the idealistic, superior Morrows handle and accept two children who assume that this must all be a trick, that they will be punished eventually, especially with no other examples to follow? And how do telepaths react to cynicism and distrust?

Tia and Rabbit’s acceptance into the Morrow community is paradoxically too difficult and too easy. Too difficult, because as the text continually reminds us, Tia, at least, has been in near constant telepathic communication with this group since infancy; some of the concepts that supposedly shock her should not be shocking her. (Seriously, in all of the images sent back and forth, and in all the times Ashira sent images of the Morrow community to her, no one sent images of birds and cats? I suppose I can understand keeping quiet about the bathroom situation, but she should have had a sense of the rest.) Too easy, because the Morrow community, for all their disdain, is often far too polite to Tia and Rabbit.

Oddly, the Morrow children completely accept Tia and Rabbit; it’s the adults that have difficulty. I say oddly, because Hoover shows enough psychological insight elsewhere in the book—and enough understanding of the ways social groups work—to know that usually the first to turn on “different” children are their peers. Here, all of the Morrow children are understanding, wave off odd statements, and make instant friends.

The adults, however, have another response. One instinctively distrusts Tia and Rabbit (and in a revealing comment, calls them “specimens.”) Even the more trusting, positive Morrow adults frequently find themselves appalled by Tia and Rabbit—although they are more careful to hide their responses. And Ashira, the leader of the Morrows, is upset when Tia attempts to heal herself through extensive reading—because this is not the sort of emotional healing that Ashira believes in.

Which means, for all of Morrow’s supposed idyllic existence, Hoover has—perhaps accidentally—created a book which showcases the flaws of any society wrapping itself around ideals, particularly in a world of scarce resources. For all of their following of the “One,” for all of their clinging to ecological and egalitarian ideals, the people of Morrow are not, after all, that much superior to the people of the missile base, clinging to their beliefs in a father god and a magical missile. They just have more stuff.

And that is what, in the end, makes the duology fascinating if more than occasionally uncomfortable reading. By placing these twin societies in a future earth of limited resources and genetic failure, Hoover was able not merely to give a rather heavy handed ecological warning, but also to study what happens to societies climbing from collapse, and show that even ideals can only go so far. It’s heady stuff for a children’s book.

Mari Ness can’t help noticing that Florida, where she currently resides, rarely survives any of these apocalypses. She wonders if she should worry.

I am not ashamed to admit that I don’t get the “Elizabeth and Essex” joke at all.

Sqwid, neither do I–I’m glad I’m not the only one!

Granted, my grip of British history is pretty weak, but wasn’t (the much older) Queen Elizabeth I courted by Essex? I don’t remember his title…

A reference to Elizabeth I and her “favorite”, the Earl of Essex.

Are you going to post reviews of Hoover’s other dystopias (The Winds of Wars,This Time of Darkness)? I loved Hoover as a child, and as an adult was disappointed to learn that almost no one else had heard of her. I’d love to see reviews of the rest of her books.

I’ve just ordered both of these.

“Interlibrary loans are a wonder of the world and a glory of civilization. “- Mori Phelps Markova

@Skwid, @aedifica, @ctkierst, and @Teka Lynn — Yes, it’s a very bad and not very funny joke referencing Queen Elizabeth I and her court favorite, the considerably younger Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex. Essex was by most accounts very sexy and hot and witty and a great flatterer and wore stockings that nicely showed off his legs and all of that sort of thing, so things went well until he seriously screwed up matters in Ireland and was later accused of rebellion. He had a lovely dramatic trial and was executed for treason. A couple of dramatically inaccurate Hollywood movies have been made about their saga.

Anyway, I’m now even more annoyed that the Morrow community is shocked that Tia and Rabbit didn’t get the joke. They’ve been living in a primitive missile silo, not studying Tudor history or Bette Davis movies, and your comments prove that, as I thought, it’s not even an obvious reference for contemporary readers.

@Lynnet1 …..maybe! Clearly she provides a lot for me to talk about, which is a plus. Not immediately, however.

@Pam Adams — Many of these posts have been brought to you by the marvels of Orange County Interlibrary Loan. I love it. Our little town library may not have many books, but our librarians are the best around, bar none.

As a kid reading Treasures of Morrow, I know what I wanted the book to be as opposed to what the book was.

First, I have to throw in some adult perspective/kid perspective on the first one. As an adult, the artificial insemination of the Silo woman with the sperm that starts all this was beyond lame. Skipping the whole bit about it being an obvious substitute for rape, we’re to believe that the first response of a person who has never seen another human being outside of his home community and who has grown up believing all other humans died ages ago responds to the earthshattering discovery of Others by knocking one out, spending two minute impregnating her, and then running off and surpressing all information about the incident.

The mind boggles.

But let’s get back to this book.

The first book is about Tia and Rabbit escaping from their home community. That the Morrows are more focused on getting the kids and getting out may seem a little iffy to me as an adult, but it seemed reasonable enough as a kid. Even as an adult, I’ll toss out some obvious excuses. The Morrows are completely unprepared to deal with an outside community. They’ve never even imagined it could happen.

But they probably have had to deal with their share of children wandering off into dangerous situations from which they need to be rescued. Given a small community where everyone knows everyone and where they all share a certain degree of telepathic connection – and given the dangers outside their main settlement – it makes sense that they would throw themselves into high gear to save two children they perceive as part of that community.

So, I can sort of buy the idea that they ran off to rescue two children but had completely ignored dealing with the community the children come from.

That’s what I expected the second book would be about, Rabbit and Tia going back to help the Silo folks. Or maybe the Morrows figuring out how to approach them.

At the very least, I figured they wouldn’t go out of their way to make things worse.

Let’s see. Not only does the Silo community now have every reason to hate and fear the Morrow community, they also should still have plenty of Morrow DNA floating around (the original “carrier” had primary rights to all females and didn’t seem shy about using it), even if (so far) we’ve only had two kids turn up with the trait, there will probably be plenty in the following generations.

Also, while the Silos may have a higher mortality rate, they have a higher birthrate and are physically better adapted to survive in the new world. The Morrows may not always have the weaponry edge. The Morrows have guaranteed that, if the groups meet again with the Silo people having the advantage, they aren’t likely to spare any mercy for the Morrows.

@ellynne — On your first point, to be fair, I suppose that Hoover had to have some way of inserting genetic telepathy into the Silo community. The problem is, as you not, the method she chose is just not plausible, quite apart from the major ethical problem — the guy would have been jumping up and down shouting “WE’RE NOT ALONE! WE’RE NOT ALONE!”

I’m less sure that the Silo community will be producing several telepaths in the future, because someplace or other Hoover mentions that most of the pregnancies started by the Major ended up in miscarriage.

But I am sure that not only will the Silo people be hostile, they will be on their way. However superior the Morrows may feel, history has shown that people exposed to advanced technology held by others will be able to replicate it if they want to/have the resources/feel threatened. (See, history of the atomic bomb.) And while the Morrows seemingly have considerably more resources, the Silo people are sitting on top of a former military base, with a lot of availble metal and necessary chemicals, and they are within walking distance of another city with more available metal. And — this is key — they feel threatened, and were already mildly paranoid. I see no reason why they wouldn’t immediately embark on a weapons program. And while it might take them some time to find the Morrows, it wouldn’t be an impossible search.

And as Tia and you both note, the Silo people are more physically capable than the Morrows. This does not bode well for the Morrows.

What this all leads to is two books with a fascinating premise/interesting ideas that just weren’t well thought out.